- Curious Matter

- Jan 21

- 2 min read

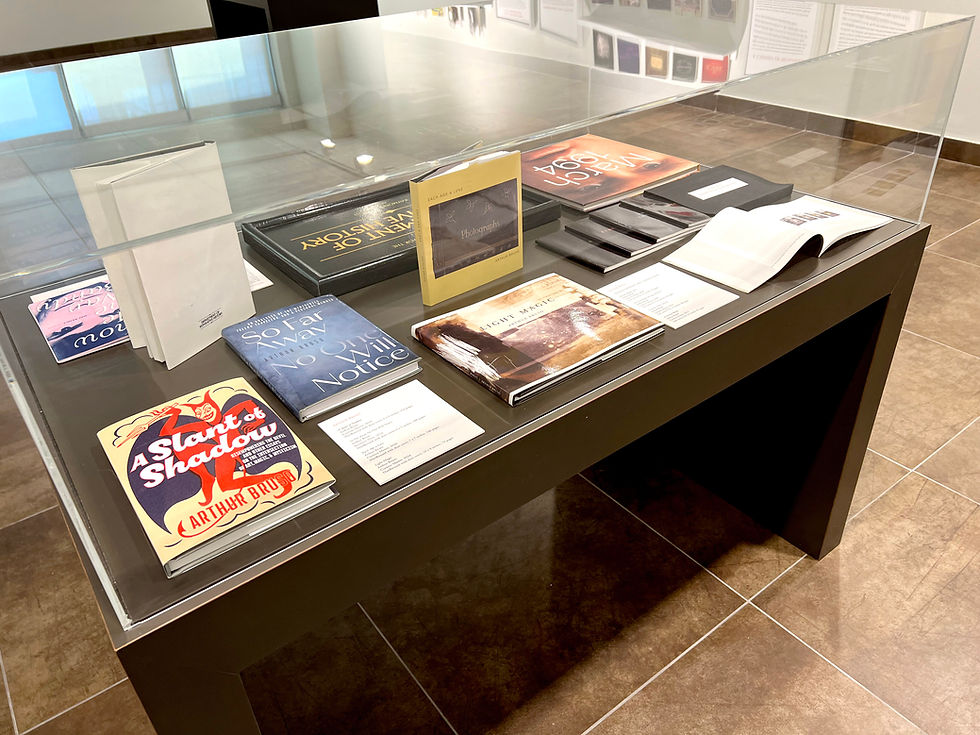

The Devil Show

An exhibition in celebration of the publication of A Slant of Shadow by Arthur Bruso

Author reading Sunday, April 27, 2025

1:00 to 3:30 pm

Exhibition April 27 - May 25, 2025

Curious Matter

272 Fifth Street | Jersey City, NJ

“The Devil Show” brings together over fifty toys, images, artifacts, and objects from Arthur Bruso’s private collection—each depicting the devil in one of his many guises. There is mischief and menace, caricature and charm. From plastic Halloween figures to vintage folk art renderings, the devil is depicted with playfulness, irony, reverence, and fear. Though not conceived as a scholarly taxonomy, the collection itself reveals patterns and peculiarities, speaking to the enduring place of the devil in the popular imagination, as well as the delight, fascination, and exuberance of the collector.

“The Devil Show” complements the publication of Bruso’s new essay collection, A Slant of Shadow, in which the author delves into artworks that function as vessels of supernatural intent. Across cultures and time, these artifacts were designed not merely to be seen but to act: to guide spirits, invoke divine power, protect, warn, or transform. In A Slant of Shadow, Bruso explores the liminal space these objects inhabit—neither fully in light nor entirely in darkness—where art intersects with magic, mystery, and mysticism.

While the book offers a contemplative and poetic meditation on the spiritual dimension of art, “The Devil Show: offers something more visceral and immediate, an unfiltered look at one collector’s fascination with a figure that has haunted, tempted, and entertained humanity for centuries.

© 2025 Curious Matter used by permission

Purchase A Slant of Shadow here.